History

- Brief History of Liverpool Hospital

- Extensive History of Liverpool Hospital (see below)

A new settlement

Governor Macquarie founded the township of Liverpool on 7 November 1810 to meet the needs of a spreading settlement. Having likely started as a tent hospital in the 1790s, Liverpool Hospital was established in a brick building on the banks of the Georges River in 1813, where it was run as a hospital for soldiers and convicts.

The Hospital had three rooms and could house up to 12 patients, who received rations of one pound of meat and one pound of wheat or flour a day. No hospital clothing was provided unless patients were near naked! Medicine in the early half of the 1800s was quite limited, with most Hospital treatments consisting of blood-letting by cupping or leeching, entices for the stomach and purgatives. Instruments for operations were carried in the surgeon's pocket or top hat, although they would have mostly dealt with medical emergencies such as epidemics, accidents and snake bites.

Construction of a larger hospital, originally designed by Francis Greenway, commenced in 1822. Due to a decrease in population size, it was closed down in 1848 until 1851, when it reopened as The Liverpool Benevolent Asylum to provide shelter to aged, infirm and destitute men.

Asylum inhabitants

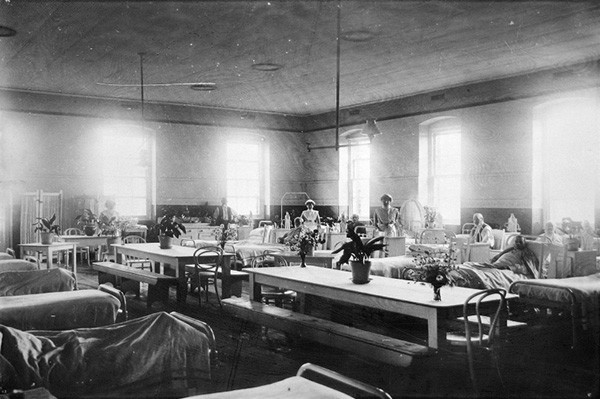

The Asylum was commonly referred to as 'the yard', with inmates expected to assist in the upkeep of the institution. They were an extraordinarily diverse assortment of characters from all parts of the world and every rank, religion and occupation. There were ex-soldiers, seamen, miners, explorers, authors, businessmen and professional men.

The majority were ordinary honest men, forced into hardship because of sickness, drink, destitution, old age, loneliness or lack of family support. Dr Joseph Beattie, Medical Superintendent of the Liverpool Asylum between 1886 and 1916, estimated that more than 10,000 men had died in the Asylum during his time there, although some individuals lived to incredible ages. John Brown was reputed to have died at the age of 130, having been a 'powder monkey' aboard the ship 'Victory' at the battle of Trafalgar.

The prominent and notorious were also there, including the son of the Archduke of Vienna; an unnamed son of a Royal Duke; the Australian writer James Tucker, author of Ralph Rashleigh; the eccentric 'Flying Pieman' William Francis King, well known for his marathon walking feats throughout the colony; James Dooley, Premier of NSW in 1921/22; and according to local legend, William Hare, the Edinburgh murderer and body snatcher.

The growth of Liverpool Asylum

In 1862, the NSW premier announced that the Government would take over management of the Asylum from the NSW Benevolent Society and appointed the first Superintendent of the Liverpool Asylum. Thomas Burnside was a retired army sergeant and a strict disciplinarian who was responsible for 403 inmates and paid a salary of £150 per annum. All manual work was performed by the inmates, who were set tasks according to their ability. They received extra rations of bread or tobacco or small allowances for their work.

Burnside remained Master of the Asylum until his death at 49 years of age in 1869. His wife Mary Burnside was appointed Matron in 1862 and remained in the position until her retirement in 1896. They had five daughters, two of whom later became assistant matrons at the institution.

Liverpool Asylum had a reputation of being the most professionally managed institution because unlike other Asylums, it had been managed by experienced medical professionals since 1871. It was therefore called upon to handle the more chronic and incurable cases such as dementia, cancer, cardiac disease and chronic ulcers.

Despite this, residents of Liverpool were becoming less tolerant of the presence of the Asylum in their town, due to the increased number of consumptive and cancer patients. In 1896 the Mayor and Alderman of the Liverpool Municipality made submissions to the government urging the removal of the Asylum from the town. "The inhabitants whom we represent complain that they are sickened to see the cancerous and consumptive men walking the streets, and other ailing patients sitting in hotels and recreation grounds," they wrote. Pressure to remove these patients from Liverpool mounted and much comment appeared in the Liverpool Herald and the Sydney Morning Herald during this period.

In 1913, under the restructured Department of Health, all health-related services were amalgamated under an administration with much wider responsibilities. These included the fully government-supported State Hospitals and Asylums which were upgraded and became hospitals for the chronically ill.

The changes reflected the need to administer a wide variety of health services for a rapidly expanding population. The state's population increased by over one million between 1900 and 1927 and the hospital was unable to keep abreast of the demands made upon it. In 1927, the Minister for Health changed the designation of the state 'Asylums' to 'State Hospitals and Homes' to avoid any confusion with the state's mental hospitals.

Liverpool was called upon to provide facilities particularly for sufferers of inoperable cancer and venereal diseases, however the outbreak of war in 1914 placed increased pressure on the Hospital and overcrowding became acute.

In 1916, the opening of a District Ward containing 30 beds was a significant event in the evolution of the Liverpool Asylum to a district general Hospital. All serious accident cases in the district were brought to the hospital and an outpatients department was established in 1916, with an operating theatre established in 1919.

Liverpool District Hospital

From the late 1920s to 1935, the Liverpool State Hospital underwent a period of considerable improvement, expansion and development, despite the onset of the Great Depression. 1929 was the worst year of the Depression for the Asylum, with 2,567 admissions recorded. The number of inmates in residence in July that year reached a peak of 893, no doubt associated with the mid-winter weather.

In 1933 major works were undertaken to the hospital, including a modern operating theatre, outpatients department, women's ward, medical superintendent's residence and a morgue. These developments transformed the Hospital into a modern hospital with the facilities to undertake a wide variety of operations.

Liverpool State Hospital closed in 1958, ending 107 years of service to aged, sick and destitute men from all parts of the world. All acute cases were transferred to the newly constructed Liverpool District Hospital which had been built adjacent to the old State Hospital.

A booming population

By May 1966, Liverpool had become the fifth largest district hospital in the metropolitan area. Each year 70,000 patients were being treated, severely taxing the capacity of the 222-bed hospital.

When the new intensive and coronary care unit was equipped in late 1970, it was said to be one of the most advanced in the world. It had been custom-built by the Medical Superintendent, Dr Dick Freyer, with assistance from Don and Dick Everett who owned a radio and electronics shop in Liverpool. Continuous observation of patients was achieved by the use of sophisticated electronic monitoring devices displaying electrocardiographic waveforms on a bedside monitor. The nurse could observe the electrocardiograph of all patients in the unit on a master console.

In May 1972, a world first orthopaedic operation was performed at Liverpool Hospital. It was a new technique for repositioning and internal fixation of bones which enabled the patient to walk. The operation was recorded on colour television for the first time in Australia by special arrangement with the equipment suppliers.

In 1974, the Don Everett Building, comprising 64 acute medical beds and a 40-bed psychiatric unit with an associated day care centre was built. In addition, a laminar flow theatre for orthopaedic surgery was installed - an Australian first. It had been developed by the American National Aeronautical and Space Administration (NASA) to filter and replace air in the theatre, sweeping away bacteria and reducing the risk of infection during orthopaedic surgery.

The word District was dropped from the name of the Liverpool Hospital in 1978, in recognition of its growing role in providing specialty services to the whole of south western Sydney.

Liverpool Hospital became the principal teaching hospital of the University of NSW in 1989 and the University of Western Sydney in 2011. It continues to have an active education programme for medical practitioners, nurses and health professionals, with a range of clinical placements available for students from universities around Australia.

Due to an increasing focus on education and the increasing population of south-western Sydney, a major expansion took place which was split into two stages of development.

Stage 1

Original development of Liverpool Hospital took place over the following years:

- 1992 - Health Services Building (Outpatient, Community Health and Academic Services)

- 1993 - Pathology (SWAPS) Building

- 1994 - Caroline Chisholm Centre for Women and Babies

- 1995 - Cancer Therapy Centre and Brain Injury Unit

- 1996 - The Thomas and Rachel Moore Education Centre

- 1997 - Clinical Building

Stage 2

A $390 million redevelopment has now been completed, consisting of the following works:

- Development of a new Clinical Building

- Civil works including new roads and a multi-storey car park for staff

- Refurbishment and expansion of the Cancer Therapy Centre

- Cancer Therapy Research Bunker

- Expanded Childcare Centre

- Grounds and landscaping

- Refurbishment of the Thomas & Rachel Moore Education Centre

- Clinical Skills and Simulation Centre

- Ingham Institute for Applied Medical Research

Source: Raszewski, C. et al (2013). 'The History of Liverpool Hospital: From early settlement to 1993'. The Liverpool Historical Society, Liverpool City Library and Liverpool Health Service.